ECONOMIC UPDATE

Investment Note

INVERSION, SUBMERSION AND DISPERSION

Written By: Dave Mohr and Izak Odendaal

19 August 2019

Global equity markets enjoyed a temporary bounce last week

when the US government said it would postpone the imposition

of tariffs on some Chinese goods, while some items would not

be taxed at all. President Trump initially planned to impose 10%

tariffs on $300 billion Chinese imports at the start of next month.

It does show that the Trump administration is worried about

the impact of tariffs on the US economy, and wants to avoid

prices on consumer items jumping ahead of the Christmas

shopping season. However, this was soon overtaken by renewed

concerns over the health of the global economy.

SUBMERSION

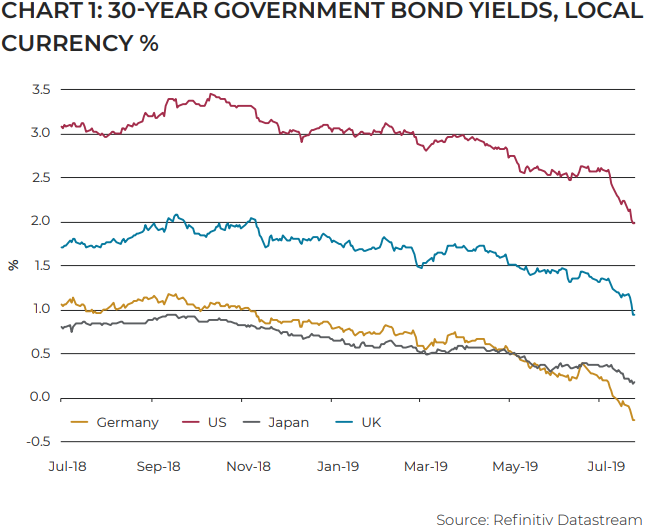

New data showed that Germany’s economy contracted in the

second quarter, which is no surprise since it is heavily dependent

on exports, particularly in the struggling automotive industry.

It is also exposed to China, where July data showed the economy

slowing more than expected, and to the UK, plagued with Brexit

uncertainty. The entire German yield curve is now submerged

below zero, screaming for the tight-fisted German government

to borrow more and spend more. But the country’s leaders

remain committed to the Schwarze Null (black zero) of a balanced

budget. In ordinary times, that might be commendable, but

these are clearly not such times.

INVERSION AVERSION

Global weakness saw a rush into the perceived safety of bonds,

with the US 30-year bond yields falling below 2% for the fi rst

time. In other words, the market expects interest rates to be

below 2% for the next three decades, an extreme outcome.

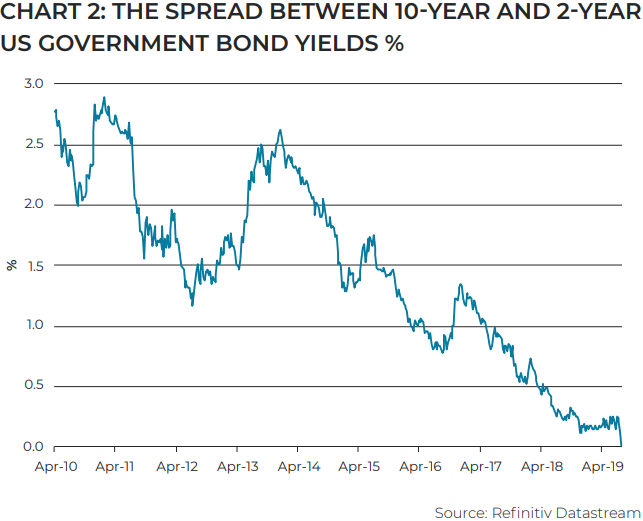

More ominously, 10-year bond yields dipped below 2-year yields

for the fi first time since 2007. This spooked the equity market

as the so-called inversion of the yield curve has preceded past

recessions. Essentially, it means that the market expects the

future to be worse than the present.

It is important to note that the inverted yield curve does not

cause a recession (unless it scares ordinary Americans to stay

at home and stop shopping). Rather, it reflects the bond market’s

expectations of near-term growth, inflation and interest rates

versus longer-term expectations. The near-term expectations

are anchored on the policy stance of the Federal Reserve (the

Fed), so that the market is effectively saying the Fed’s rates are

too high now and it will be forced to cut rates.

This creates a dilemma: on the one hand, you shouldn’t ignore

the bond market, and the most dangerous words in finance

are said to be “this time is different”. On the other hand, this

time might really be different. No other tried-and-tested

recession indicator is flashing red, and the collapse in bond

yields in Europe and elsewhere must surely play a role in

dragging US yields down. These, after all, are now the highest

yields in the developed world. Canada, Australia, Britain and

even politically-unstable and highly indebted Italy have lower

yields than the US.

This also reflects the relative strength of the US economy. All

the latest reports on the US economy show healthy levels of

consumer spending, supported by a strong job market, low

inflation and low-interest rates. The US manufacturing sector,

along with those in other major countries, is struggling. Despite

President Trump’s efforts, the trade wars seem to have hurt

rather than helped US manufacturers in total (though some

will have benefited). But this is a small part of the services-driven

US economy. The trade wars are also causing pain in other

countries, notably China, where industrial production growth

in June was the slowest in decades (but still strongly positive).

CUTTING IN DROVES

Central banks are of course already cutting rates in droves, with

Mexico the latest major economy to do so. The US Fed is likely

to follow suit at its September meeting. The market will want

to see not only a cut from the Fed, but the guidance that future

cuts would also happen. These rate cuts will not do much to

stimulate new borrowing since global debt levels are already

so high, but will ease the pressure on existing borrowers.

Importantly, central banks will act to prevent a repeat of 2008

when market stress impacted the real economy as credit

channels seized up.

How will the SA Reserve Bank respond? It has already cut rates

once, but this was just reversing November’s hike. The recent

sell-off in the rand might preclude it from cutting at its next

meeting, but oil prices have also pulled back. The Reserve Bank

will also be viewing the deteriorating fiscal position with some

alarm. However, in the current context, the widening budget

deficit is not inflationary, since it is bailing out Eskom, not

stimulating domestic spending. Ultimately, the Reserve Bank

is likely to follow other central banks and lower rates.

DISPERSION

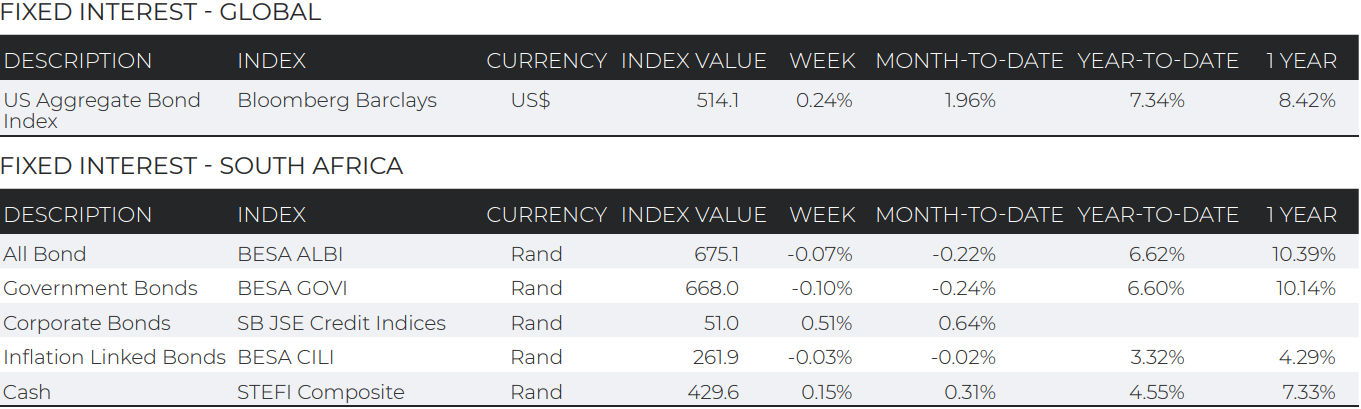

This is because in the global dispersion of real interest rates,

South Africa is now close to the one extreme, with Germany

at the other. As global fixed income yields plummet, South

Africa has gone in the other direction. Foreign investors have

pulled money out of the local bond market, worried that

government borrowing will rise dramatically to fund Eskom.

The tabling of a draft National Health Insurance (NHI) bill has

not helped sentiment either. While it has noble objectives, it

would entail potentially hundreds of billions in additional annual

outlays upon planned final implementation in 2026. (The

estimated costs and funding mechanisms have not yet been

announced.) With markets already questioning South Africa’s

fiscal management, the timing was not great. Realistically

though, it is hard to see how such a complex restructuring of

such a large and important sector can be achieved in seven

years, and a more piecemeal approach seems likely.

But a lot of the pessimism is surely overdone. While government

debt is rising due to Eskom and weak tax revenue growth, the

government is far from bankrupt. The increased talk of South

Africa turning to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for

assistance is also misplaced. The IMF itself sees no reason why

we can’t sort out our own problems without its help. It has

noted that the asset side of the government’s balance sheet

is larger than the liability side, but the assets need to be ‘sweated’,

or sold, to deliver a decent social or economic return. The IMF

helps countries that run out of dollars to repay debt or fund

imports, usually when capital flows dry up. South Africa’s

government debt is mostly rand-denominated and there is no

sign that it is struggling to fund itself in the local bond market.

The flexible exchange rate takes care of the rest. South Africa

is not Argentina, dependent on borrowing abroad in dollars.

Argentina turned to the IMF last year (for the biggest bailout

on record) precisely because the lack of a domestic bond market

means the government borrows in dollars. However, last week

its financial markets suffered a sharp collapse – currency, equities

and bonds slumped between 30% and 40% overnight – after

the reformist President Macri lost a key indicative vote ahead

of October’s presidential elections. Much like President

Ramaphosa, Macri tried to clean up a huge mess left by his

predecessor. However, the medicine he prescribed was too

bitter for the people of Argentina, but not bitter enough from

the point of view of the markets, who have been fleeing

Argentinian assets for the past 18 months. Now it appears Macri

is on his way out, to be replaced by a populist who investors

fear will make things worse, while promising to make things

better.

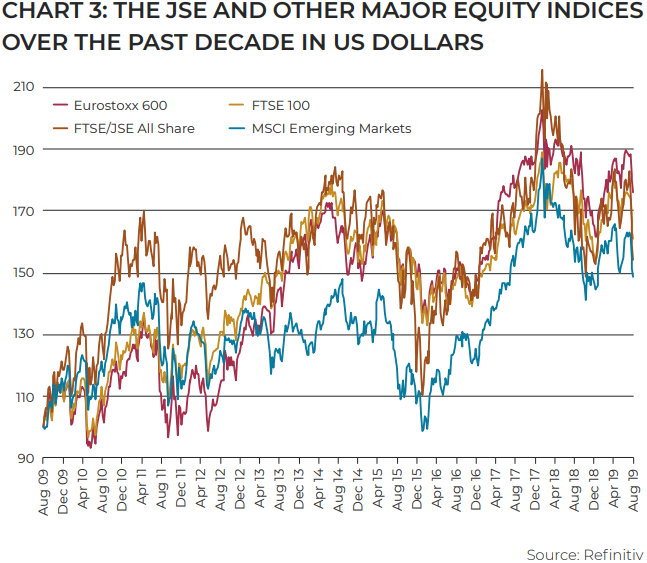

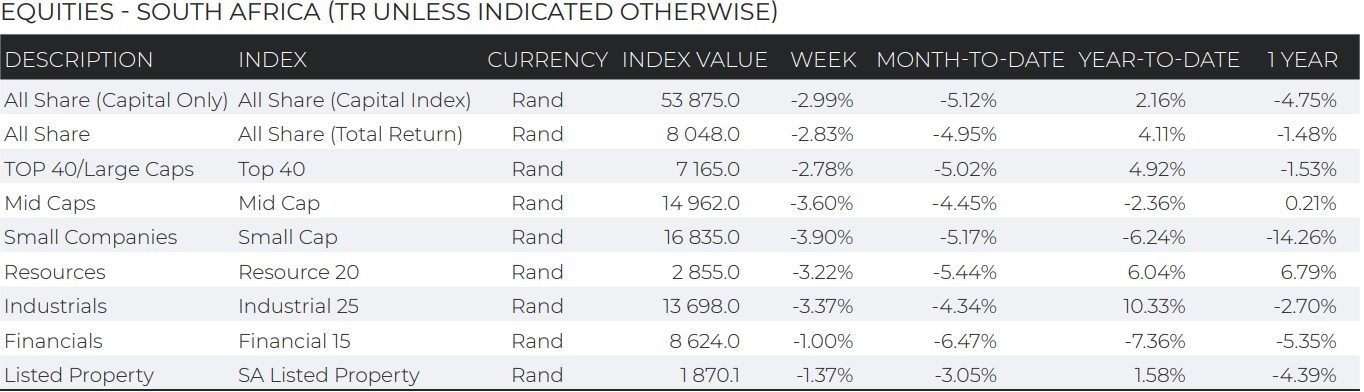

THE JSE IS NOT THE ECONOMY

It is easy to connect the dots between all this local political and

economic uncertainty and the continued poor performance

of the JSE, but this connection is overstated. In fact, the JSE

has been hit by a perfect storm of events, and virtually everything

that could go wrong seems to have done so in the past three years. The JSE has also performed in line with other non-US

stock markets over the past three years and longer, a period

where only US equities have performed really well (see chart

3).

There is no question that the weak economy has hit

domestically orientated shares, and the NHI bill is another

example of policy uncertainty weighing on share prices (this

time of medical insurers). But more than half of the earnings

of JSE-listed companies is generated outside South Africa. The

global presence of local companies has also increased over the

past few years, with Reserve Bank data showing that domestic

companies invested almost R500 billion abroad over the past

seven years, but without much to show for it. There are several

examples of poor offshore acquisitions, with Woolworths,

Truworths and Famous Brands standing out.

Crucially, JSE exposure to the high-flying US market is low,

while exposure to the UK is relatively high. Overall, the global

exposure of the JSE is concentrated, and subject to company-specific issues.

For instance, Sasol’s problems caused another

sharp pull-back in its share price last week. Last year it was the

40% decline in British American Tobacco and 20% decline in

Richemont. All three are big components of the local benchmark.

This year, only Naspers and mining companies have performed

well, the latter can still largely be viewed as a recovery from the

pre-2016 rout in commodity prices, with the weak rand also

helping.

Usually, an equity market sell-off is accompanied by a decline

in interest rates, so that shares become more attractive and

fixed income less. This has happened globally, but not locally.

In fact, high rates are just one of the reasons why local equities

have struggled. Both short and long-term fixed income yields

stand out like a sore thumb in the international context and

offer very attractive real returns. However, the risk remains that

in viewing the poor performance of the JSE as a South Africa Specific story, investors become so mired in pessimism that

they assume it can never recover. Domestic shares already price

in a very gloomy medium-term outlook for the South African

economy and can positively surprise on any evidence of a

slightly improved outlook and a rebound on global equity

markets.

Date

August 20, 2019

Author

The Wealth Room

Share This Project

Tags: finance, financial coaching, Grant van Zyl, Old Mutual

Leave a Comment